Header image source: Excerpts from page 22 of the Environmental Investigation Agency’s report titled A System of Extinction: The African Elephant Disaster (1989).

Military & Corrupt Officials

Of all the people contributing to the demise of wildlife and ecologies around the world the corrupt individuals serving in their country’s national parks, military, and government are the most untouchable. In some cases the military may be instructed specifically to carry out wildlife crimes and use military resources to poach elephants (page 58). Protected by military power or the corrupt officials that secretly support them, the individuals that abuse their positions and dip into the wealth of their country’s natural resources do so purely for their own gain and at everyone’s expense.

Over the past few decades corrupt government officials have played a large part in allowing criminal syndicate members throughout Eastern and Southern Africa to traffick wildlife parts and even aid poaching and trafficking suspects. Law enforcement officials have even been implicated in thefts from secure stockpiles and of trafficking ivory themselves. Diplomatic immunity and government ties have also been abused by a number of individuals to openly transfer wildlife products out of Africa. As recently as 2013 Chinese officials were linked to illegal purchases of thousands of kilograms of ivory.

For more information on national and transnational efforts to stop environmental crimes please see our section on Environmental Crime Operations.

British Kenya (1888-1962)

The EBUR report (file link), produced in 1974, notes in its first appendix a variety of illegal activities undertaken by British and Kenyan officials and civilians. These acts were witnessed or corroborated by informants known to the author of the report, Ian S.C. Parker. Among the named officials accused of illicit activities during the 1960s are:

Superintendent of Criminal Investigation Department (Kenya Police) D. Baker: Destroyed evidence relating to four foreigners who had illegally killed elephants.

Game Warden D. Allen: Took ivory from official registers and then passed the ivory off as his own or belonging to his friends. They claimed to have a license to shoot elephants, but could not produce the license when asked by officials.

Senior Game Department Clerk M. De Souza: Responsible for signing permits for the sale of elephant tusks, he stole £30,000 ($84,224 in 1960) worth of ivory and was sentenced to three years of probation on the basis of not being as senior as other suspected corrupt officials who warranted investigating. His supervisor, Chief Game Warden W. Hale Esq., retired from the Game Department and left the country before De Souza was prosecuted.

Kenya (1963-1978)

In July of 1963 Jomo Kenyatta became the first Prime Minister of an independent Kenya, then served as president from 1964-1978. His party, Kenya African National Union (KANU), would become the dominant political force in the country for forty years. But almost immediately corruption took root and political gifts were dispensed.

In the mid 1960s Kenyatta personally gave permission for a former general of the Mau Mau Uprising, an insurgency that lasted from 1952 to 1960, to sell wildlife parts that had been gained during the “freedom fight.” Presidential orders allowed him to sell £75,000 worth of ivory without oversight from the Game Department. The general would claim in 1973 that President Kenyatta was intending to or had already given ivory to former insurgents as a form of reward.

In 1972 President Kenyatta’s family became openly involved in the ivory trade. The United Africa Corporation, which his daughter Margaret was a major shareholder of, would export more than 50,000 kilograms of ivory to Peking, China (today Beijing), a third of Kenya’s total export for that year. In 1973 and 1974, in spite of a national ban, the company continued to sell ivory overseas that allegedly came directly from government-held stockpiles.

During this period Kenya’s President and his wife Ngina Kenyatta amassed extraordinary personal assets including as much as 2,000,000 acres of land, financing, and money directly from the United Africa Corporation. $600,000 was spent on 21 houses in London in 1973/1974, purchased in cash by Ngina Kenyatta.

Corruption would continued to plague Kenya’s wildlife conservation efforts and by the end of 1979 there were 47 high-ranking members of Kenya’s Wildlife Conservation and Management Department under investigation out of a total of 77 wardens.

Kenya (Present)

An independent study examining 743 in-progress or concluded cases (page 11) between January 2008 and June 2013 showed that individuals found guilty of wildlife crimes in Kenyan courts were rarely getting a substantial fine even under the new laws. Poor case management including: improperly gathered evidence; missing, stolen, or insufficient evidence; as well as other problems experienced by police or prosecutors resulted in 15% of defendants in 202 concluded cases having their case withdrawn or dismissed (page 13).

During this period 1,543 kilograms (3,401 pounds) of elephant ivory and rhinoceros horn was presented as evidence (page 14). Despite the severity of their crimes against elephants or rhinos, fines were given to 68 of the 72 offenders (94%) (page 14). Fines levied against those found guilty of wildlife crimes involving elephants and rhino accounted for about 2.7% of the value of the confiscated ivory and horn. Offenses involving rhinos and elephants made up 37% of the crimes reviewed by the study.

Most wildlife crimes committed during the period of the study were against animals used for bushmeat or for trade in their skins (page 12). Of all the individuals found guilty of a crime, more than 70% were given a fine, of which almost all of them were able to afford (page 14). 91% of these fines were of KSh 40,000 ($650) or less (page 15). Only 4% of all convicted individuals were sent to jail (page 13).

In December of 2013 Kenya enacted the Wildlife Conservation and Management Act (WCMA) 2013 which substantially increased penalties that could be imposed by judges on individuals found guilty of a wide range of illegal hunting, trafficking, or possession of wildlife products. Fines can now be in excess of KSh 20,000,000 ($200,000) in the most severe cases, compared to a maximum fine of roughly KSh 40,000 ($464) under the WCMA 1976 law (PDF) and subsequent amendments. A Wildlife Crimes Prosecution Unit was also formed to prosecute cases specifically relating to illegal wildlife exploitation.

Corrupt police, judges, and prosecutors who accept bribes, steal evidence, and traffick wildlife products remain a problem in Kenya, which is one of Africa’s two largest departure points (page 49) for illegal ivory heading to Asia. In March of 2016 four Administration Police officers, Constables Peter Kuria Kimungi and Martin M. Marangu along with Corporals Francis K. Karanja and Stephen Chege Ngawai, were charged with the illegal possession of 5 kilograms of ivory which they may have been attempting to sell.

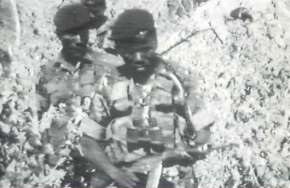

On 2 September, 2016 three individuals (pictured), including a captain in the Zambian Defence Force, were arrested in Malawi on charges of dealing in government trophies and illegal possession of three elephant tusks as well as lion and leopard skins. The trophies were believed to have come from South Luangwa National Park in Zambia, but were confiscated in the Malawian town of Mchinji located on the country’s western border. On 30 September, the first case in a new public-private litigation project saw John Sakala, Ronald Mawale, and Captain Sandu Kalimbo each sentenced by the Malawian court to 40 months in jail. No option of a fine was given.

Zimbabwe’s red beret paratroopers,

implicated in wildlife poaching.

Photo: EIA – A System of Extinction

In the 1980s Zimbabwe and South Africa were among the largest African opponents (page 21) of the international ivory ban that would be formally agreed to by CITES members in 1989 and go into effect soon after. However their elephant (page 21) and black rhinoceros populations (page 20) were dwindling from rampant poaching from foreign and domestic poachers. Independent organizations conducted rhino population surveys and estimates throughout the 1980s and early 1990s and showed that estimated rhino populations had declined to 2,138 individuals in 1989, far below what the country’s environment would be able to support (page 21). Dozens of rhino carcasses were being reported by authorities each year, even in the country’s prized national parks (page 22), and became an embarrassing issue that the Zimbabwe Wildlife Department attempted to refute and ignore (page 21).

In 1988 the first allegations of Zimbabwean military involvement in poaching were published (page 21). Military and government agencies were among the few that had access to interior regions which experienced high elephant and rhino poaching. Zimbabwe’s “Red Beret” paratroopers, trained by North Korea, were implicated in the poaching crisis along the country’s eastern border where they were engaged in a protracted battle against Mozambican rebels (pages 21, 22). Throughout the 1980s a number of shipments of rhino horn and elephant ivory have left Zimbabwe via North Korean diplomats and attachés, relying on diplomatic immunity and government ties to avoid trouble (page 22). Some of the rhino horn made its way to North Yemen (page 22) which along with Aden and South Yemen (page 8) imported a sizable share of East Africa’s declared exports beginning in 1964 and eventually was consuming as much as 40% (page 9) of the world’s rhino horn market by 1977.