Buyers of Pangolin Scales

Introduction

Pangolins are a family of eight mammalian species and are unique among all other mammals for having armor-like scales made from keratin, the same family of fibrous proteins found in the horn of a rhinoceros or the fingernails of a human. There are four extant species of pangolins in Asia forming the family Manis and four extant species in Africa forming the families Phataginus and Smutsia. Not much is known about their behaviors and habits and up until recently it was believed that all pangolins are nocturnal. However conservationists in the field have recently suggested that at least some pangolins will forage during the day. All pangolins have extremely long tongues, nearly the length of their body, a specialization which helps in consuming insects. Also called “scaly anteaters” because ants and termites make up the majority of these armored mammals’ diet, they consume so many insects when foraging that they naturally regulate the population levels of social insects locally. Pangolin species that spend time in trees are believed to have fully prehensile tails to assist in climbing.

Pangolins have been hunted and illegally exploited for centuries by people interested in their scales and meat. Over the years pangolins have had varying levels of international protection against exploitation, but since 2017 all eight species have been listed on CITES Appendix I to afford them the highest protection against commercial trade. Yet all species of pangolin continue to be illegally exploited and trafficked, primarily for use in dubious traditional folk medicines but also as a luxury meat.

The four African species of pangolin and their distributions (shown in the image on the right): black-bellied pangolin (Phataginus tetradactyla) (magenta), white-bellied pangolin (Phataginus tricuspis) (yellow-green), giant ground pangolin (Smutsia gigantea) (green), and Temminck’s ground pangolin (Smutsia temmenicki) (blue).

The four Asian species of pangolin and their distributions (shown in the image above): Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla) (orange), Indian pangolin (Manis crassicaudata) (violet), Philippine pangolin (Manis culionensis) (red), and Sunda pangolin (Manis javanica) (cyan).

For more reports and publications specific to the pangolin, please visit our Reports index and the Pangolin Specialist Group’s library.

Driving Demand & Prices

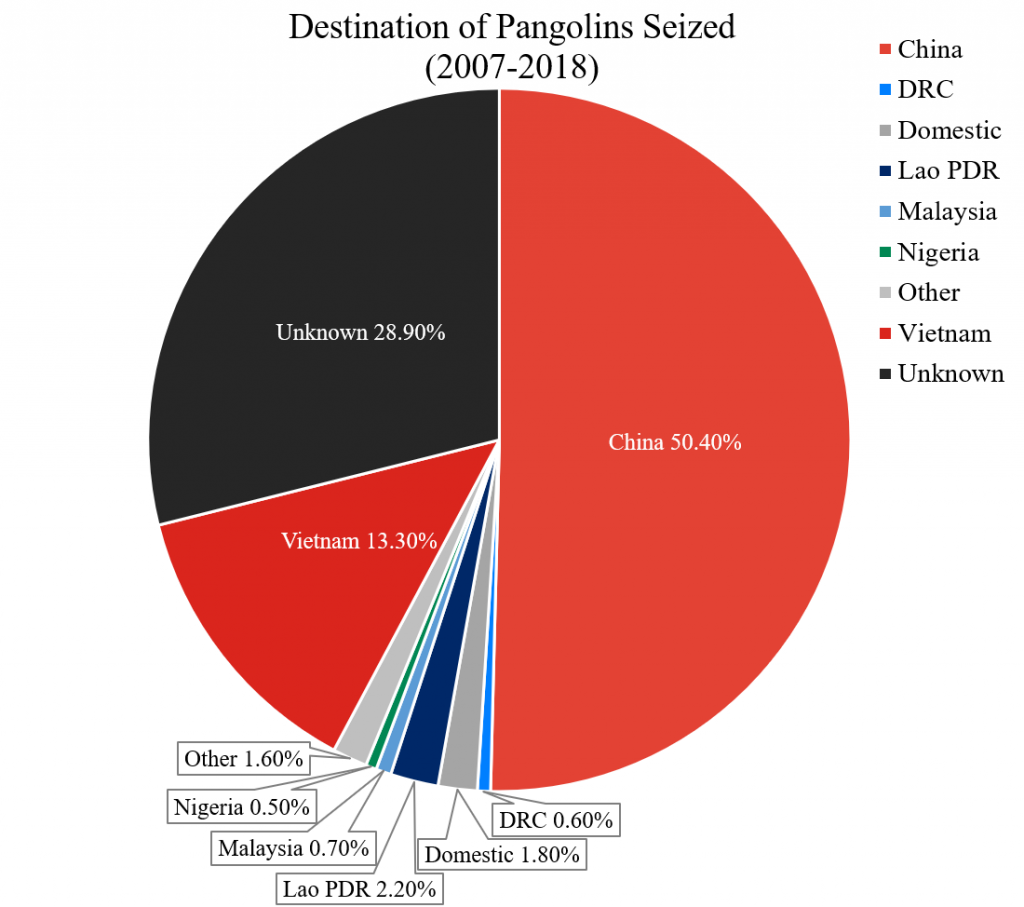

There are two primary countries responsible for driving demand in pangolin scales, meat, and other parts. China is a major importer and also a final destination of illegally obtained pangolin scales and meat as well as live animals. A significant amount of these imports go toward supplying the pharmaceutical and folk medicine industries (page 7). In a 2014 report the IUCN SSC Pangolin Specialist Group concluded that “[c]onsumers in China have, since the mid-1990s, been driving regional trade in pangolins and their parts.” This assertion is backed by increasing data correlating trade routes for pangolin scales, live pangolins, and in whole carcasses trending towards Chinese consumers living throughout Southeast Asia and specifically to China itself (pages 3-4).

Like China, Vietnam has consumers who view pangolin meat as a status symbol and its scales as essential folk medicine despite unproven benefits. Until at least 2008 Vietnam was considered to be primarily a transit country for pangolins and their parts (page 3), however its role shifted to that of a major importer (page 15) while still acting as a transit nation for the illegal trade. In 2016 the country was believed to have become a substantial consumer of pangolin meat and scales (page 3). While the lion’s share of shipments seized in recent years were destined for China, in 2019 the majority of pangolin parts internationally trafficked had Vietnam as their destination (page 10).

Prices of pangolin parts in China have risen dramatically from 2008 to 2017. In 2008 live pangolins once sold for $80 per kilogram (~$36 per pound). In 2017 live pangolins could command a price of more than $200 per kilogram. Over the same time period the price of scales increased from $300 per kilogram to $600. In Vietnam a kilogram of scales sold for roughly $250 (~$113 per pound) (page 14).

Primary and Secondary Threats to Pangolins

Experts have been surprised by the scope of exploitation occurring in every known pangolin range state across two continents (page 19) as well as the size and frequency of internationally trafficked shipments. Recent studies have shown that documented cases of pangolin poaching have been increasing since the 1990s, likely due to a depletion of the species in China where recent demand has been greatest. In China from the 1960s through the 1980 an estimated 160,000 individuals were hunted, legally or illegally (page 19), with some estimates higher (page 14). As of a 2017 report, researchers suggested that worldwide populations had already begun declining (pages 6, 8) and that Asian population declines had been noticeable at a regional level since the 1990s (pages 2, 8, 13). It is believed that continued demand, along with the recent historical depletion of pangolin populations of Asia, is the cause for an increasing trend in exploitation in Africa (page 19).

For many years habitat loss, especially for the Sunda pangolin in Asia (page 1), had been considered the leading cause of these species’ assumed population declines. Habitat degradation and destruction continues to be a major risk to all pangolins, some of which are arboreal while others live in underground burrows. Additionally, all eight species are believed to have low reproductive rates and a low rate of replacement within their habitats, making any reduction in their populations a long-term contributor to population declines. All pangolin species are considered to be timid and apparently share the same defense mechanism of curling into a ball, shielding themselves with their keratin scales. It is therefore likely that poaching of any pangolin species is relatively easy (page 4), especially with dogs (page 8), and is a much lower-risk activity than the hunting or trapping of dangerous high-value wildlife like tigers and various species of rhinoceroses and elephants. In part of their Malaysian range it is believed that Sunda pangolin are opportunistically hunted by indigenous groups without the use traps or weapons and this hunting is a major concern of the species’ continued survival (page 4).

In the 2000s over-exploitation for bushmeat and poaching were identified as the clear, primary threat throughout pangolin range states in Africa and Asia. Demand for their parts is believed to be increasing (page 15) and poaching remains the most serious threat to populations of Sunda pangolin in Borneo (page 1), Philippine, Indian, and Chinese pangolins, but is also believed to be the greatest threat to all species of African pangolins. Sunda pangolin species have been protected domestically since at least 1931, however exports from Indonesia and Malaysia of more than 60,000 kilograms (132,277 pounds) of scales from 1958 through 1964 have been documented (page 44) and seizures in these areas continue to be made. In early February 2019 the Malaysian authorities in Sabah, a state on the island of Borneo, announced a record seizure of nearly 30,000 kilograms (66,100 pounds) of meat and scales. At the beginning of 2020 Malaysian authorities took down a smuggling syndicate and also seized about 6,000 kilograms (13,200 pounds) of pangolin scales.

Both legal and illegal logging as well as other major causes of deforestation occur in pangolin range states such as Indonesia; Africa’s Congo Basin where gorillas are also threatened; and Malaysia where orangutans are threatened. Habitat and forest conversion occurs in some areas of these range states where both legal and illegally operating palm oil and rubber plantations deforest large swathes of land and replant them with saplings.

A report published in 2009 described the secondary threats to live pangolins after being seized from illegal traffickers. The removal of these animals from their natural habitat, lack of food and water, and then exposure to the sustained stress of being smuggled is believed to leave these animals in poor physical health by the time they are intercepted. With little knowledge of their specific dietary and health needs, law enforcement authorities were unable to provide proper care for the animals before re-releasing them into the wild or transferring them to a wildlife reserve. The same report also suggested that little or no planning was undertaken before release nor was monitoring of the animals performed afterwards (page 4). It is known that some pangolins suffer from skin infections and parasites due to their captivity and transport, but can also have much more serious and life-threatening problems (page 18). There is no data on the survival rates of individuals after being released into the wild or what effect, if any, they had on wild populations after experiencing human contact.

Legal Trade, Domestic Protections, & Exports Under CITES

The international pangolin trade has been documented irregularly since the early 1900s with much of Asia’s demand being sourced from Asian nations (page 44). Despite legal protection in some countries dating back to at least 1931, researchers have concluded that the demand for pangolin scales, estimated at tens of thousands of kilograms per year, have exceeded what Asia is capable of supplying (page 44) and is impacting regional and global populations. As a result, international treaties protecting the species and regulating commercial trade have changed substantially over the years.

Since 1975 all four Asian species of pangolin have been listed in Appendix II of CITES, granting limited protections relating to international from commercial trade (page 44). African species of pangolins have been variously listed across CITES Appendices I, II, and III since 1975, however most remained on Appendix II until recently. The inclusions of these species had attempted to protect it from exploitation for international trade, but did not regulate certain trade for domestic use or sale. Before and since then, some countries have taken steps on their own initiative to enact legislation to regulate their domestic pangolin trade, but with little effect when enforcement is weak.

Indonesia implemented protections for its native Sunda pangolin species as early as 1931, however like many protections by other nations it does not seem to have been enforced meaningfully. One report documented the export from Indonesia and Malaysia of more than 60,000 kilograms (132,277 pounds) of scales from 1958 through 1964 (page 44). In India, similar domestic protections were enacted for its two native species in later revisions to the Wildlife Protection Act (1972). Both the Indian pangolin and Chinese pangolin are currently listed on Schedule I, however they are still poached for profit, illegally traded and consumed locally within India (page 33). Vietnam did not introduce a law completely outlawing domestic hunting and trading of both of its two native pangolin species until November 2013 (page 3) and as of 2019 is a major consumer and transit country for illicit pangolin meat and scales (page 50). Despite bans on trafficking, in 2019 Vietnam emerged as the primary destination, but not necessarily the end-point, for the majority of pangolin parts internationally trafficked according to seizure data (page 10).

China’s domestic protections and enforcement began in 1989, and have been subsequently revised many times. However the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Wildlife (also sometimes translated as “Wildlife Protection Law” – independent translation) has been considered a means of supporting the use and trade of wildlife and their parts, rather than a regulation of wildlife exploitation for the health of the environment. While wildlife with special protections are prohibited from being sold or purchased (Article 22), “scientific research, domestication and breeding, exhibition or other special purposes” are allowed by special approval or authorization. This led some experts to conclude that recent Amendments by the Chinese government have the purpose of broadening regulatory meanings to allow for the farming of tigers and bears as well as the continued domestic trafficking of many wildlife species for use in traditional folk medicines as well as the pharmaceutical industry.

In 2000, CITES introduced a “zero export quota” for Asian pangolins, effectively prohibiting all international trade for commercial purposes (page 33). However it was not until 2017 that all species of African and Asian pangolin were formally listed on Appendix I of CITES, placing a complete ban on their commercial international trade.

To emphasize enforcement of wildlife laws, Cameroon, Indonesia, and other countries have publicly destroyed their stockpiles or large-scale seizures of pangolin parts. For details, read Pangolin Scale Stockpile Burns ►

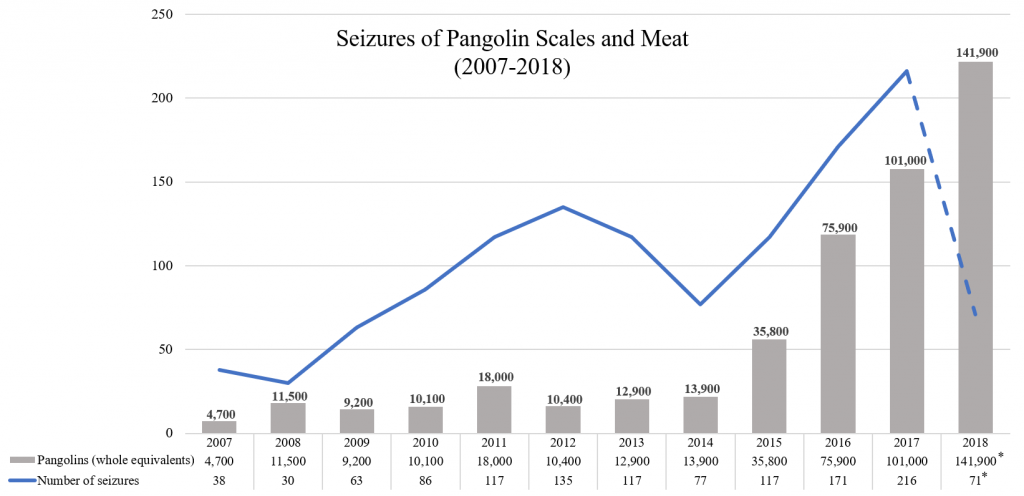

Seizures of pangolin scales and meat in select African and Asian

countries beginning 2007. *Data for 2018 is not fully complete.

Source: World WISE & UNODC.

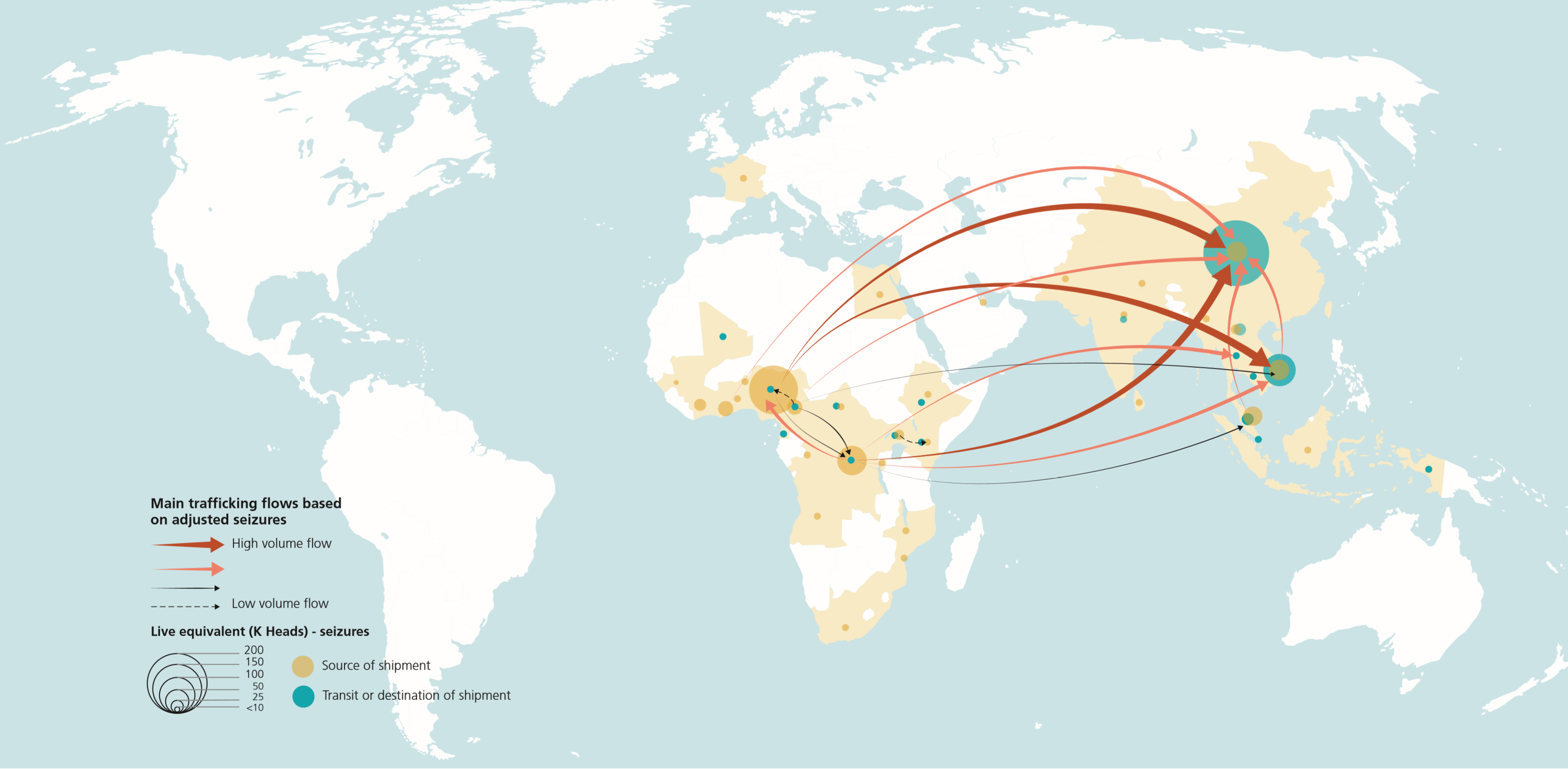

Transnational Trade & Supply Chain Since 2000

China became dependent on external sources of pangolins in the 1990s and Southeast Asia became the most convenient source (page 14). Seizures of illegal shipments departing from Southeast Asia made up a significant portion of all recorded seizures around the world. From 2000 through 2012 and possibly into 2013 Southeast Asia, most notably Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand, continued to supply pangolins for the Asian market while acting as entrepôts (pages 7, 10). China remained the most common destination for seized shipments of pangolin parts through 2018, but in 2019 Vietnam was the destination of choice (page 10).

Seizure data since 2013 reflects a dramatic change in sources and destinations, with both legal trade within Africa and trade from Africa to Asia increasing dramatically. By 2015 fewer than half of seized shipments recorded Southeast Asia as their point of origin. Africa became the next substantial source of pangolins for the Asian market and from 2016 through 2018 Central and West African nations were the origin of more than 80% of pangolin shipments seized (page 7). In contrast, a negligible number of shipments were seized originating in Southeast Asia from 2016 through 2018 (page 8). Confiscation of shipments since 2016 revealed an increase in the proportion of pangolin scales trafficked compared to meat (page 7) and correlate to an increase in demand reported for pangolin scales in China and Southeast Asia (page 10).

Based on shipments seized, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, and Uganda emerged as major transit countries within Africa since 2013 while also becoming direct suppliers to Asia (page 8). Nigeria has a history of acting as a transit country for illegal goods and swiftly grew to become the largest staging ground for pangolin scales in Africa. In 2017 Nigeria was declared as the origin of shipments totaling 9,000 kilograms (page 8). The next year saw 27,000 kilograms seized. In 2019 Nigeria became the most common point of origin of in the global pangolin trade when at least 51,000 kilograms were seized globally with the country declared as the point of origin (pages 7-8). Despite its neighboring countries reliance on trade, Nigeria controversially closed its borders in October of 2019 to stem the flow of all types of smuggled goods. By March 2020 authorities in Cameroon had marked a change in the flow of smuggled medicines, household items, and basic commodities, largely out of Nigeria. It is not yet clear what impact border closures and tighter enforcement had on the illegal wildlife trade into Nigeria or how its trade partners will be influenced by the needs of illicit suppliers in West and Central African.

The amount of pangolin scales and meat seized globally increased more than 10-fold from 2014 through 2018 (page 6). During that period an estimated equivalent of 370,000 pangolins we seized (page 3), though that represented only a fraction of estimated global trade (page 6). However, the number of seizures globally from 2014 through 2018 increased only gradually (pages 5-6), reflecting a certain success by authorities in detecting large shipments of suspicious provenance or illegal content. In 2019 three major seizures took place in Singapore that amounted to the equivalent of more than 20,000 pangolins each (page 6).

The fundamental means of trafficking pangolin parts have not changed and have close ties to the ivory (page 9) and tiger parts trade (page 17). However the outbreak of COVID-19 (Coronavirus) hampered illegal trafficking routes in early 2020. Undercover investigators were told by brokers trafficking ivory and pangolin scales that the temporary suspension of trade between Vietnam and China made trafficking difficult (pages 12-14). In some cases traffickers may have risked bringing illegal wildlife products overland without going through an official border crossing (page 13). Stockpiles of illicit ivory have been accruing in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam since China’s increased enforcement of wildlife trafficking laws. The Wildlife Justice Commission believes that stockpiling of pangolin scales is occuring in Vietnam, both due to increased enforcement in China and because of transport difficulties caused by COVID-19 (page 5). During the period January through March 2020, Wildlife Justice Commission’s undercover investigators were offered more than 22,600 kilograms (49,800 pounds) of pangolin scales by brokers in Vietnam (pages 3).

End-consumers of Pangolin Meat, Scales, & Parts

African folk medicine (muthi, muti, or juju) as well as bushmeat poaching account for at least some local demand of pangolin meat and body parts. However documented poaching as well as seizures suggest that traffickers in Africa are buying up locally-caught pangolins primarily for export to Asia (page 2). As the scale of poaching has grown more noticeable, so have the supply routes leading out of African nations (pages 2, 16). It is possible that the bushmeat poaching of pangolin presently occurring in Africa is statistically significant, however it is clear that the majority of demand for meat is coming from Asia (page 16).

China’s yearly consumption of scales from 2008 through 2015 was estimated at an average of 26,600 kilograms (58,643 pounds) (page 7). This number is roughly in line with the 25,000 kilograms (55,116 pounds) annual domestic consumption of pangolin scales for medicinal products as recommended by China’s State Forestry and Grassland Administration (pages 7, 9). These scales were allocated to ‘infused products’ and patented medicines, which were both recognized usages under the law. However the 25,000 kilogram quota greatly exceed the volume of pangolin scales legally imported by China in any given year from 2001 through 2015. Although it is unclear what number of pangolins are provided from domestic Chinese sources, it is known that there are no provinces issuing hunting licenses nor are there any successful breeding programs (page 7). According to researchers investigating imports “between 2001 and 2014,” Chinese companies reported only 7 legal imports of pangolins or their scales for commercial purposes. These imports came from Africa and Asia and totaled more than 6,248 kg (13,774 pounds). An additional 2 imports were of specimens and hunting trophies claimed to be for educational purposes. Like the consumption statistics, China’s commercial import statistics do not match up with data described by legal exporters and omit more than 1,030 kg (2,270 pounds) of pangolin scales (page 4). This suggests that illegal international trade have been the primary means of supporting these domestic industries for many years, possibly with secretive stockpiles being used to fulfill demand.

Investigators have found as recently as 2016 that both retail and online stores openly sell pangolin scales in China for use in traditional folk medicines (page 8). The folk medicines claim to promote blood circulation, stimulate lactation in women, disperse swelling, and expel pus (page 1). Some also claim that it treats psoriasis, however like many traditional folk medicines there has been no confirmation of these benefits. Consumption of pangolin meat at home, at important events and gatherings, and in restaurants is also a display of social status and wealth (page 1). An investigation into Shuidong’s trafficking syndicates, in China’s Guangdong province, found that pangolin scales were being sold or traded to dealers who were selling them on to pharmaceutical companies in China’s folk medicine and pharmaceutical industries (page 5). In a survey conducted by WildAid in 2015, 3,000 people were asked about whether they consumed pangolin meat or parts for any reason with 70 percent believing that the animals’ parts had medicinal value (page 20). This was a much higher percentage than in Vietnam, where only 8 percent of the 815 respondents surveyed believed with certainty that pangolins had medicinal value (page 22). In China the treatment of rheumatism features as the most commonly alleged medicinal benefit, but the treatment of skin diseases, swelling, and asthma also feature prominently. Some respondents also believed that pangolin parts could treat cancer and promote lactation (page 20).

In India, as of 2015, pangolin parts were still being used in traditional folk medicines and their meat eaten as a delicacy (pages 33, 38). This tradition probably continues, but given the extent and direction of trafficking is unlikely to be the cause of the majority of pangolin poaching in the country (page 34). Folk medicines in these regions make use of the scales, meat, skin, nails, and bile of pangolins in an attempt to treat a variety of symptoms or to prevent certain types of inflammation including pneumonia. Some tribal people in the Indian state of Odisha wear rings made of pangolin scales as decorative items, which may be a traditional practice (pages 38-39).

Vietnam is considered a major consumer of pangolin parts (page 14) and in 2019 became the largest destination or transit country for pangolin parts destined for Asia (page 9). Like China, some people in Vietnam view pangolin meat as a status symbol and others claim that its scales are essential folk medicine ingredients even though its medicinal benefits are dubious. In some cases, restaurant owners have told investigators posing as potential customers that the scales have no medicinal benefit at all (page 19). An investigation by EIA in 2015 found that some restaurants serving pangolin meat in notable Vietnamese cities such as Hanoi and Hai Phong claimed to have served city government officials (page 19). Even when Vietnamese authorities know about restaurants selling pangolin meat, they are rarely shutdown (page 22).

Pangolin parts are also being sold online on Vietnamese-language websites and, like elephant ivory, rhino horn, and hornbill casques being sold online in Asia (page 2), are sometimes advertised under code words (page 53). In December 2015 WildAid conducted a survey in Vietnam that asked 815 people whether they had ever purchased pangolin products and what they believed it was good for. Only 4 percent of respondents had ever purchased pangolin products, but a variety of products had been consumed including pangolin wine, meat, prescription medicines, and blood. Only 8 percent of respondents believed that pangolin parts had medicinal value, while 64 percent were undecided but had heard about alleged medicinal benefits. The respondents most commonly believed that pangolin scales increased sex drive, treated rheumatism, or treated asthma (page 21).